Vidriera (For Josiah McElheny) (2013)

Vidriera (for Josiah McElheny) is a performance work that reinterprets the 1613 short story El Licenciado Vidriera by Miguel de Cervantes. The piece was developed for the Wexner Center for the Arts in conjunction of Josiah McElheny’s exhibition “Toward a Night Club”. The event, organized by Richard Fletcher and with the participation of McElheny and others, was entitled “The Cave of Light: A Dark Symposium” and was presented on April 1, 2013.

There are many stories about personal tragedy, many stories about the lessons of anti-heroism. There are countless tales about those who affect the world almost by accident.

There is an infinity of biographies, both true and fictional, of minds who, by breaking with the conventional patterns of thinking, brought new light onto the world, and many of those doing so at a high cost to their own lives.

Yet of all those stories, few are as tumultuous and opaque as the story of a transparent man, as written by an author who had a similarly tumultuous and opaque life: Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, also known as el manco de Lepanto — the one-armed man of Lepanto (as he lost one limb in a Battle of that name). After completing the first part of Don Quixote, Cervantes wrote a number of short stories, known as novelas ejemplares, from which there is this one story.

We are in Seventeenth century Spain. Our protagonist is Tomás Rodaja, an orphan with no property or money to his name, and a past of which he himself either is ignorant about or has willingly forgotten.

He is nonetheless talented, loyal, and hard working, and these skills are noticed by a couple of noblemen who take him unto their mentorship. It is in this way that Tomás manages to go to law school in Salamanca, the most illustrious university of the time, and a bright future awaits him. However, the hopeful Rodaja has no idea of the extent of unwelcome luminosity of that future that eventually, and unexpectedly, comes to him.

It so happens that a young woman falls in love with Rodaja. He shows no interest, his mind set onto other things at the time. In desperation, this woman attempts to cast a love spell on him by inducing him to drink a certain love potion.

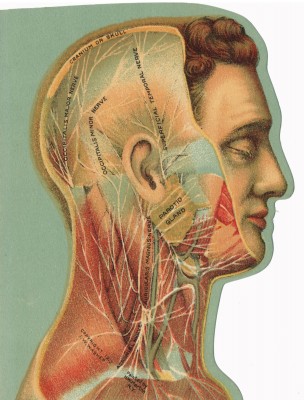

The potion fails to work, but while Tomás does not fall in love, he does become deadly ill as a result. His head feels as if it is on fire; he experiences convulsions; some believe he won’t survive. He remains in bed for six months. In the end, he miraculously recovers and re-emerges physically sound; however, by effect of the potion he is now a completely different person: he is profoundly delusional.

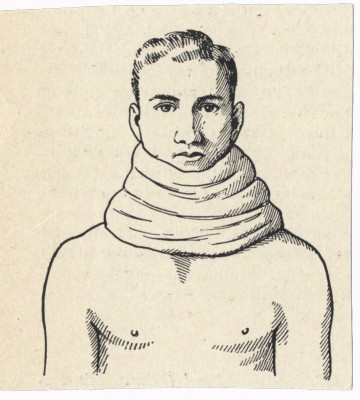

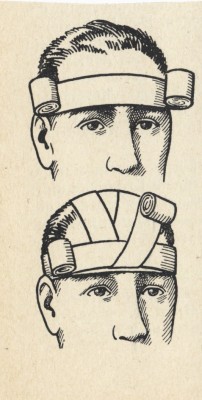

Mainly he firmly believes that he is entirely made out of glass, from head to toe. He thinks of himself as fragile as a delicate figurine. No one can get close to him; he only eats very soft and bland foods, and drinks with a long straw; during the summer he sleeps in the open field, afraid that if any object were to accidentally fall on him it would shatter him completely; during the winter he sleeps inside a stable amidst a mound of hay.

He needs to wear large, unfashionable felt outfits and often needs to be carried around on a cart full of straw, surrounded with glass objects to alert others of the fragility of his condition. By observing this eccentric behavior those around his town conclude that Tomás Rodaja has lost his mind, and he eventually receives the nickname Licenciado Vidriera, the Glassman bachelor.

But had Vidriera’s interactions only been limited to expressing this eccentric delusion, he would probably not have been remembered to this day. It so happens that Vidriera also starts making observations around people and the world about him, some of which are so poignant and so on the mark that non withstanding his glass obsession, he proves to be more lucid than anyone around him.

To any subject that Vidriera is approached he has something witty and true to say. Of poetry Vidriera states that it is such a high and difficult art that no known good practitioners exist. Those who call themselves poets are so bad that they don’t even count. Those so-called Poets, Vidriera says, are so self-centered that if someone doesn’t understand their poems they always conclude that the fault is in the public. So-called Poets, for Vidriera, are like shoemakers: they had never made a bad shoe- the defect was always in the foot.

He ridicules specialists as vulgar people who can only talk to each other in their internal language, useless outside of their own world. Of those who are professionally unsuccessful he says that they are poor out of their own decision because there are always rich women or men who they can seduce and marry.

Of painters he is no more generous: for Vidriera those who are supposedly good only imitate nature which is always superior, and the bad ones, instead of imitating nature, throw it up as in vomit.

Of muleteers, or businessmen, he says: they have divorced with their bedsheets and married their saddle; they are so much in a hurry that in order not to lose the day they will lose their soul. This is Vidriera’s seventeenth century diagnosis of Wall Street.

Of the hypothecary, or pharmacist, he says they are the enemies of candles, because a candle is a simple solution to light a house. Instead, pharmacists replace the simple and cheap remedy to expensive and harmful ones, sometimes even having the opposite effects of the simple medicine. This would be Vidriera’s diagnosis of today’s pharmaceutical companies.

Not so much different with doctors: no one is more harmful to the republic, Vidriera says, than they. While judges twist justice to their benefit, Doctors benefit from our decay and sickness, and the sicker we become, the better. This is, as you may have already gathered, Vidriera’s view on today’s health insurance industry.

But Vidriera made observations also on the human character as well. When he is asked: what do we do to get rid of envy? His response was: go to sleep, as that is the only way in which you will reach similarity with that who you envy. While awake you will always be lesser since you focus on envying others instead of in being yourself.

While referring to a lazy tailor, He sarcastically praises those who do nothing, saying they are on their way to salvation. Since few people do their job without lying or cheating, they always end up as sinners. So to do nothing is to be rewarded with heaven.

He similarly comments on the rich of course. When Vidriera met a rich and ostentatious woman with a very ugly daughter carrying a lot of jewels, he says: its good that you have layered her with stones as she now has become a well cobbled stone street over which horse carriages can cross.

Privilege, to him, is perhaps the worst attribute one can have as an artist. Of comedians and actors, he says, there is nothing worse than to be well-bred, as you will have absolutely nothing to say.

Who in the world, then, Vidriera is asked, is a lucky being in his mind? He says: “nobody”, as nobody knows God, nobody lives without a crime, nobody is happy with his fate.” Furthermore, the more virtues one expects of someone the more sins they will make.

People then ask Vidriera: “You find faults in everyone. Who in the world, then is a lucky being in your mind?” He replies: “nobody”, because of the simple reason that nobody knows God, nobody lives without a crime, nobody is happy with his fate.”

Despite the fact that Vidriera screams at the slightest touch, and despite of his irrational fears and his extravagant eating, drinking and sleeping habits, he quickly becomes a glass oracle, and eventually is brought to royal court as such to display his wit.

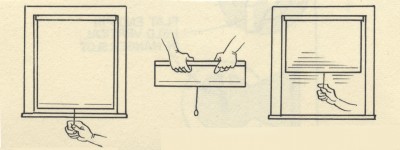

Finally a friar from the order of San Jerónimo takes pity of Vidriera and takes upon himself to cure our hero. After a few weeks of treatments, he finally succeeds in this task. The cured Vidriera, dressed again as a distinguished gentleman comes back to court. He changes his name to Tomás Rueda, to sound more distinguished.

Soon he is surrounded by his many admirers, who quickly start asking him a myriad of questions as before. What does he think of doctors? Of the rich? Of liars? Of the vain? But he has no witty answers to them. He announces that he is no longer the same; that he is now a sane man, with nothing special to say.

The crowds, in disbelief, continue to follow and pester him regardless, to the doorsteps of his house, overwhelming him with stubborn questions. They don’t want him to be normal; they want the eccentric character that in his madness unveils the truth. They need answers. He disappoints them; and they would not let him exist as a conventional human being.

Vidriera then sees that he can no longer live in peace, nor quietly pursue his once-hoped life in law. He then leaves the court and, not knowing where else to go, joins the army and the battlefield, where he dies a hero’s death in an obscure battle in Flanders. And thus our story abruptly concludes.

Which leaves us with a series of opaque problems and unresolved questions. Why does Vidriera so quickly give up his attempt to be a “normal” being? And why in contrast he is so keen to survive while inhabiting such an intolerable body, and yet is so keen to stop living when, in health, he confronts the expectations of others. Finally, Cervantes doesn’t tell us why Vidriera thought of himself as made out of Glass, as opposed of any other material.

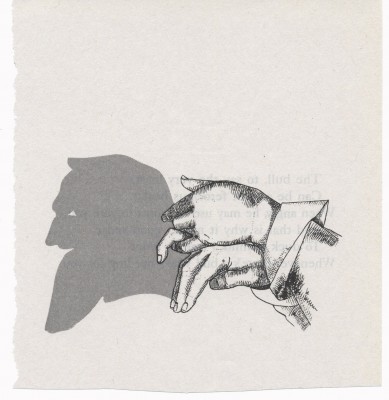

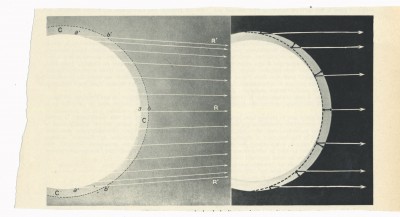

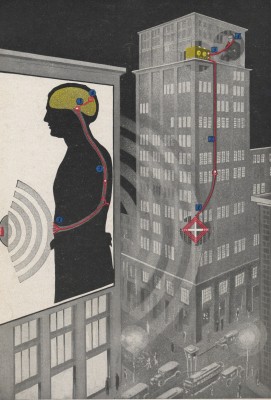

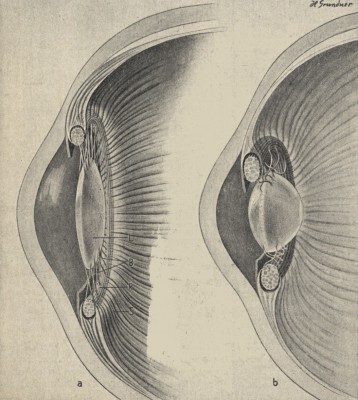

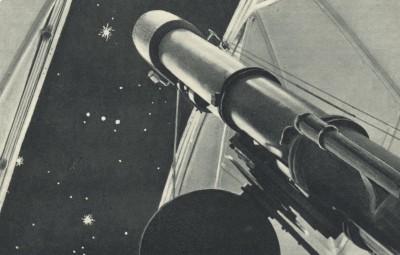

But in a way, no pun intended, it is crystal clear: the transparency of glass allows us to see; magnifying glass allows us to perceive the details when others see the whole and using it as a telescope it allows us to see the totality when others only see the immediate surroundings.

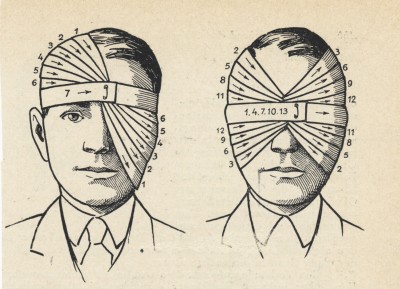

Vidriera saw it all through his multiple lenses of social penetration; he was deemed insane and through that insanity he was oddly liberated to say what he wished without the censure that comes when we speak our mind and we haven’t observed the rules we have been imposed.

But he paid a price to this. As much as he thought he had suffered, when he was “cured” he realized his restored health, his restored consciousness, only made him witness to his inability to see or utter truths anymore, and, more damning, he was presented with a plethora of admirers who still sought him regardless of what he had to say. This intolerable form of life makes him engage in the riskiest of jobs, which is to join the army, as if he saw no other solution to the purpose of his life than to end it.

Poor Vidriera! Perhaps his fate was a revenge of the painful truths he inflicted, as the Spanish saying goes: “he who has a glass roof, should not throw stones onto the roofs of others.” And yet he didn’t choose this fate, but was made victim of it by someone who he didn’t love.

By becoming the fascination of the crowd, he was miserable. When we seek notoriety and influence, we don’t understand how isolating and lonely that place is; we also lose our humanity. We become a circus oracle, a strange bird to be observed with the purpose of entertaining others.

Perhaps we all aspire to be of glass, to attain the alchemical transparency of this material; but we can’t handle the consequences that such transparency entails. It is a treacherous material, as a liquid that yet looks solid.

One of the most memorable lines by the greatest Spanish poet, Francisco de Quevedo is: “las columnas de cristal al temple de amor sustentan”, the columns of glass sustain love; Luis de Gongora, his rival, wrote, “al sonoro cristal, al cristal mudo” (the sonorous glass, the silent glass), and Quevedo again, “era de vidrio y quebrose/para conmigo acabóse” (out of glass it was made, with me it broke forever.”

Perception is a glass column, like water, the sonorous glass, it flows, like beauty, the silent glass, it shines, but it is always precarious and there is no way in which we can arrive to such pure vision without having to pay for it.

What we should fear the most, perhaps, is to lose our fear of fragility, because it paradoxically will be then when we will be more fragile than ever, and our desires will lie shattered, only left with a human body of which all can be done is to dispose of in a random battle; a battle that we don’t believe in.

Tags: anti-heroes, Cervantes, classics, Eccentrics, Idealism, Identity, literature, Nonsense, Perception, Utopia