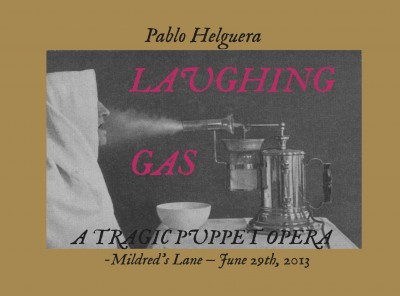

Laughing Gas (2013)

Laughing Gas is a performance incorporating puppetry, theater and song, first developed and workshopped at Mildred’s Lane in the summer of 2013. The piece narrates the true history of the discovery of anesthesia and the dramatic life of those who were associated with its discovery. The piece is written for a narrator with a musical background three musical interludes, and a puppet stage where the various characters and scenes are portrayed throughout the narration.

The production of “Laughing Gas” was realized with the research assistance of Lizzie Hurst and the work of Sharon Romang. The fellows and staff of Mildred’s Lane staged the puppet play.

LAUGHING GAS

1.

[soundtrack: Shenandoah (introduction)]

2.

[Marching through Georgia Lament]

Ladies and Gentlemen: the following story is not for everyone. Only for those of you who have experienced happiness and sadness, those of you who have imagined a life only defined by pleasure, those of you who have dreamed to live a world without suffering, this story is for you.

This is the painful story of the eradication of pain, and the curse that surrounded all those who attempted it.

We are in the winter of 1844. Medicine, while having made great advances, still confronts one of its greatest hurdles: there is no way to prevent pain during surgery. As a result, surgery is treated as a very last resort and expert medics are set on the idea that the future of medicine lies exclusively on medicaments, not external intervention. Yet in hospitals the two most common procedures are removal of tumors and severing of extremities. The screams and pain emerging from the operating rooms from those procedures are intolerable; many young medical students abandon the profession after being part of such operations. The unimaginable pain, the unspeakable agony, is expressed by a patient of the time as follows:

“suffering so great as I underwent cannot be expressed in words…the blank whirlwind of emotion, the horror of great darkness, and the sense of desertion by God and man, bordering close upon despair, which swept though my mind and overwhelmed my heart I can never forget. …I still recall with unwelcome vividness the spreading out of the instruments, the twisting of the tourniquet, the first incision, the fingering of the sawed bone, the sponge pressed on the flap, the tying of the blood vessels, the stitching of the skin, and the bloody dismembered limb lying on the floor. Those are not pleasant remembrances.”

3.

[Kingdom coming]

Around the same time that this unspeakable agony goes on inside hospitals, a man named Gardner Colton from Vermont, appears announced in several newspapers, as a prominent lecturer that presents a Grand Exhibition of the Effects by Inhaling Nitrous Oxide”. Nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas, was discovered by Joseph Priestley and published as part of his Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air of 1775. In 1800, scientist Humprey Davy suggested that this air could have analgesic qualities, but his suggestion lied buried in a book for 44 more years. Through those years, the gas was used at parties amongst the British upper class and medical students, merely for entertainment. These demonstrations were usually mayhem; after inhaling, people would roam around the theater laughing, jumping, singing silly songs, tripping all over. Here is one of such songs of the period:

4.

[Song: “If you only got a moustache”]

5.

[Marching through Georgia]

So we are at Gardner Colton’s exhibition tour, where he shows the effects of nitrous oxide, and where all participants are invited to inhale, to experience euphoria and laughter. Colton travels the country with his large exhibition.

On December 10th, 1844, Gardner Colton arrived to Hartford, Connecticut, to present his laughing gas demonstration. Amongst the audience was a young dentist named Horace Wells. Wells was an ambitious, imaginative, slightly naïve and timid fellow, who was captivated by Colton’s lecture. And so one of Wells’ friends, Sam Cooley, tripped very violently, badly injuring his legs. Wells noticed that his friend was bleeding badly from the legs. When he pointed it out to Cooley, he looked down and continued laughing; he hadn’t noticed nor was he feeling a thing.

That was Horace Wells’ epiphanic moment of his life. He thought, if someone inhales this gas and becomes insensitive to a wound, why couldn’t this be used in extracting a tooth without inflicting the usual terrible pain?

And so he put his hands to work at once. The following day he summoned his friends, getting a hold of a bag of nitrous oxide of his own and proposed a tooth extraction- of his own- after he inhaled the gas. Surrounded by everyone, he inhaled the sweetish gas, opened his mouth, and the tooth was extracted. He barely felt a thing.

Everyone would later go back and look at that day as the birth of anesthesia.

6.

[Ashokan Farewell]

But if only the world were so easy, if only explanations for things were so straightforward, if only someone could truly eradicate pain from the world. Pain, in fact, would take revenge on Horace’s effrontery, of his attempt to challenge nature in its own game.

Enter William Thomas Green Morton, another young dentist from Massachusetts. A young man with a dark past as a swindler in California, a past that no one in the east knew about at the time, he was ingenuous however, and had become known for soldering false teeth onto gold plates. He had arrived to Hartford making a small partnership with our hero, Horace Wells, a young and brilliant dentist.

Wells starts applying his new laughing gas system onto his dental patients. Even though he is still perfecting his approach, 10 out of 12 patients don’t show any signs of pain after a tooth extraction. Wells is exhilarated. The question becomes: should he patent his discovery?

No, Wells says. The cure for pain should be as free as the air that it is is made of.

7.

[palmyra schottische]

Propelled by his own success, on January 1845 Wells embarks to do the litmus test of medical science: a demonstration of his system at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. A medical student volunteers to have a tooth extracted. All the doctors, some the best physicians of the time, gather with curiosity to see this discovery. Most are skeptical. Few believe it is possible at all to ever eradicate pain, without killing the patient. If it indeed works, it would change medicine forever.

Wells needs to get some Nitrous Oxide from a local provider in Boston; the gas may be different from the one he has used at home, and the behavior of the gas may be different due to the temperature and other conditions; so many things can go wrong, and Wells’ reputation is at stake.

At first there is only silence. Wells applies the gas to the patient, and goes on to work extracting the tooth. Everyone looks in expectation. Wells turns to the patient, inserts the instrument in the mouth. Then turns around. The tooth is out!

But wait. There is a noise. The patient has made a noise, hasn’t she? Some kind of grunt? It is unclear what it is.

[laughter ]

But right after that, it doesn’t matter anymore. Everyone in the room starts to laugh. “the patient screamed they say.” “humbug” “humbug” they cry.

7.

[Shenandoah]

Wells is devastated and he runs out of the room. The gas has failed, he thinks.

In the middle of the commotion, the person who people pay least attention is the patient. She sits there claiming that she didn’t feel a thing. But it is too late; the laughter of the room drowns what the patient is saying, the laughter of the room drowns the historical discovery of the laughing gas. Instead, Horace Wells has been now labeled a humbug, and this man, who has such low self-esteem, decides that minute that he will retire from the practice of medicine forever.

[marching through Georgia]

But there was someone else in that room who wasn’t laughing either. William Thomas Green Morton had observed the incident carefully. He knew that Wells was onto something, and he had now abandoned it. There was a huge unclaimed discovery for the taking and Morton would take possession of it. Morton, always a scoundrel and a professional swindler was ready to conduct a new fraud, stealing Wells’ invention.

For it, however, and to preserve a sense of distance, he though about using Ether, a slightly different substance from laughing gas, as his medium. He performed it first on his dog Rig, and concluded upon seeing the unresponsive animal that no pain would be felt by the use of this gas.

8.

[weeping sad and lonely]

In 1846, Morton was able to convince the chief physician at Mass General to conduct a public demonstration like Wells had done a year before, this time with a new substance that would completely eradicate the pain. He took pains not to reveal that he was using sulfuric ether, and even added oil of orange to conceal the all too familiar smell of ether amongst doctors.

But Morton as we know, was not a true physician, nor a scientist. So he had to consult a real one to ensure that he was following appropriate procedures.

For this, he turned to Charles T. Jackson, a most renowned physician of the time and mentor at some point of Morton. Morton wasn’t sure how to administer the gas, and Jackson led Morton to the use of a flask with two valve openings where the patient could inhale the substance.

And with those preparations, the grand day for Morton took place, his moment in the limelight. He was almost half an hour late to the surgery, making all physicians wait, as he waited for the glue of his haphazardly made flask dry. There was no lack of suspicion amongst the college. How can a guy without a doctor degree, how can a man without any apparent knowledge of medicine, carry the ultimate cure for the profession?

And yet, there it is. The gas was applied. The patient turned to the doctor. The tumor is removed.

Did you feel any pain, Morton asks the patient?

No.

Aleluya!

[kingdom coming]

Ladies and Gentlemen, finally the moment has come, says Thomas Green Morton. Finally the most painful, the most gruesome of operations, will not be felt by a patient, says Thomas Green Morton. Childbirth, removing a nose tumor, sawing limbs off, extracting all the teeth of a mouth, opening a chest, all can be now done without a second of pain, says Thomas Green Morton. And who has brought you this discovery? Who for the coming generations and the next thousands of years, whether if you twist your ankle or have bladder stones, when do you don’t shed a single tear upon surgery, who would you thank? Who is the master of pain? Thomas Green Morton, Thomas Green Morton. Me, Thomas, Me, Green, Me, Morton, the master of insensitivity, the harbinger of bliss, me, the benefactor of humanity, leading the world to the eternal dream of pleasure, as the Chariot driving us to heavenly bliss!

9

[Choir: Swing Low Sweet Chariot]

10

[Jeanie with the light brown hair]

But oh, if only, if only things were so easy, if only a single sniff of a magic substance would allow us to eradicate pain completely. And Pain, we all know, is a vindictive spirit. It doesn’t like it to be ignored, it always strikes back with overwhelming force in the least expected ways.

Morton, always scheming to make money in indecent ways, knows the value of his magic discovery. He will never reveal the true content of the compound that causes insensitivity, to the frustration of the medical community. Instead, he will seek to patent his discovery and make millions of dollars from it. Morton approaches a writer, Oliver Wendell Holmes, to help him find a name for his new invention. Holmes proposes “anesthesia”, from the greek “unfeeling”.

Except for one small detail: his patent may not have credibility. The US patent office won’t accept a patent claim from an unlicensed doctor.

He then turns to his former mentor Charles T. Jackson, who is a renowned scientist in medicine, mineralogy, chemistry, and who can give full credibility to his patent application. Also Jackson is politically connected, as he was the brother in law of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Morton offers Jackson to do a joint patent application, and he is delighted when Jackson accepts. Nothetheless, Jackson has an agenda of his own.

Charles T Jackson is a curious fellow with a particular pattern: all his life, he would usually claim to have made a discovery in competition with the actual discoverer. He claimed to discover guncotton, the material later used to create photographic film, he contested the invention of the telegraph with Samuel Morse, the discovery of the digestive action of the stomach, and other geological discoveries. Little did Morton know that Jackson would be more than happy to steal Morton’s discovery in the same way that Morton had stolen it from Horace Wells.

Morton manages to get a patent for his invention, amidst the general condemnation of the entire medical community, who accused him of being greedy and inhuman.

11.

[old folks at home]

Meanwhile, at the Connecticut General Assembly, sensing the injustice made to their native son Horace Wells, and unbeknownst to Wells himself, the lawmakers passes a resolution declaring him as the sole discoverer of anesthesia. A war is on: who is the true discoverer of this substance: the man who the medical community laughed at and called a humbug, the greedy scoundrel who first demonstrated the effects of ether but seeks to capitalize from the patent of the discovery, or the elder scientist who claims to have discovered every other discovery of his time? Is it the naïve, is it the evil one, is it the arrogant one?

[beethoven’s 7th]

Speaking of which: where was Horace Wells? Little did he know that now his invention, stolen from his former dentist partner, was making money. Wells had moved to Paris and is trying to make a living as an art dealer, selling reproductions of Michelangelo drawings. He has left medicine completely , trying to forget the painful episode of his discovery of eradication of pain.

Wells had become errant, wandering around aside from selling art, also selling canaries and household items. He goes to New York, where he decides to go back to experimenting, reflecting that there has to be an alternative to ether or laughing gas. He starts experimenting with chloroform. At the time, the effects of sniffing chloroform, a highly addictive substance, were not known. Wells is to find out to himself, and in this search of the complete eradication of pain, he is going to encounter the worst pain possible himself.

Days and nights of experimentation with chloroform, sniffing, searching for pain, sniffing again. After a few weeks, he has become addicted. Reality and fiction are no longer distinguishable, his extremities feel numb, then his vision and hearing begin to fail. In the height of his delusions, he becomes deranged, and walks out onto the street with a bottle of sulfuric acid that he throws to the clothes of two prostitutes. He is taken to New York’s Tombs prison where he realizes what he has done. He writes a last letter:

“What misery I shall bring to my near relatives, and what still more distresses me is that

my name is familiar to the whole scientific world as being connected to an important discovery, and now , while I am scarcely able to hold my pen, I must bid all farewell. May god forgive me…Oh my god, my god protect my family… I cannot proceed. My hand is too unsteady and my whole frame is convulsed in agony. My brain is on fire.”

Horace Wells asked the police to let him to go his house to pick up his shaving kit as he went to prison. Once in his cell, Horace Wells picked a vial of chloroform to inhale one last time, while he cut the arteries of his leg with a blade. And in that blissful state, as he bled away, Horace Wells, 33 years old, the discoverer of anesthesia, the man who found insensitivity to the world and was not properly credited in life for his feat, was now gone, thankfully, at least, in a painless death.

12.

[my old Kentucky home]

But the evil ghost of Pain should not stop its revenge on the poor and hapless Horace Wells. It had other victims to descend upon; those other individuals who had claimed to have dominate it; who had called themselves its master, the self-proclaimed authors of the key to the extinction to pain. No human should ever make that claim; no such audacity should go unpunished.

And so William Thomas Green Morton would experience his own set of misfortunes. Even though his patent was accepted, it is never implemented. The United States government is the first one to break its own law by the emergency use of anesthesia by medics in the battlefield during the civil war. The recognition, and remuneration, from his patent starts becoming Morton’s obsession and will haunt him for the rest of his life. His patent expires and congress refuses to renew it nor to compensate Morton for his discovery. He is turned down in four attempts to receive credit for his discovery.

In june 1868, The Atlantic Monthly, the most respected magazine in the country, published an article about etherization. We can only imagine what Morton must have thought when reading what the article said: “the discovery was made by Charles T. Jackson, MD of Boston”… and making the only reference to Morton in the article as follows: “William TG Morton, a dentist of little medical and almost no scientific knowledge.”

That final judgment must have been the dagger in Morton’s heart, the indescribable pain that no painkiller could have ever erased. His wife said of him reading the article: “it agitated him to an extent I had never seen before.”

Morton was irrational. A month after that article, July 1868, while in New York City, on the middle of a heat wave, William T G Morton was walking by Central park with his wife one night. Inexplicably, he broke away and plunged onto a pond. He was pulled out by two policemen and rushed to the hospital, where he was declared dead of “congestion of the brain”. His death had been as messy as his life, a dishonest series of actions that placed him in a dubious place in the history of medicine, putting in question the possible contributions he had made to the discovery of anesthesia.

13.

[old folks at home]

Surviving Wells and Morton was Charles T. Jackson, but not in great health. Now in his seventies, Jackson was descending into mental illness. He was placed in an Asylum in Massachusetts, where he spent his last seven years, living the end of what a friend called “ a life embittered by a lack of appreciation for his services to humanity and ungrateful indifference to his merits.”

Adding insult to injury to the memory of these three wretched men, was Crawford Long, from Georgia, who years later wrote in the Southern Medical Journal that he had administered sulphuric ether to a patient several years before any of these experiments, in 1842. His claim, making him to some, effectively the discoverer of anesthesia. Which brings up a number of questions: what is the true claim of authorship, those who make something first, or those who announce it first, those who attempt it independently first or those who most successfully complete those first attempts?

A few things, however, are true: no one is the exclusive owner of pain or the absence of pain. The human body and the human spirit are not puppets that we can control, that we can dominate and tell them what to feel, when to feel.

And to fight pain, to attempt to dominate it, may only provide a temporary reprieve; suffering and discomfort caused by illness or injury, or even by our own imagination, all that is an inextricable part of being human, of engaging with life, with the great care and trouble of living. To attempt to eradicate our spiritual pain is ultimately to detach from the world, and it is not so different from detaching from life itself.

This is the way it is meant to be, and we might as well embrace this unwelcome guest in the deep river of feeling that is the human spirit.

14.

[Choir song: Deep River]

END

Tags: anesthesia, community art, Mildred's Lane, puppetry, Romanticism