On the Future of Art (2013)

On the Future of Art is a project consisting in a performance lecture, an installation and a published text. It revolves around an autobiographical anecdote relating to encountering a book entitled “Sobre el futuro del arte” in Mexico City in the 1980s, a book that inspired to a good degree my pursuit of contemporary art. Many years later, working at the Guggenheim Museum in New York nearly twenty years later, where my job was to organize the museum’s lectures, I encountered the original publication in English, “On the Future of Art”, discovering then that it was a compilation of lectures organized in 1969. The circularity of the experience becomes a springboard to reflect on the aspirations and expectations that we often place on art.

[PH]

[excerpt]:

Mrs. Wilson, a character in Robert Altman’s film Gosford Park, a head housekeeper in an English mansion, says

the following words in a climatic moment:

What gift do you think a good servant has that separates them

from the others? It’s the gift of anticipation. And I’m a good

servant. I’m better than good. I’m the best. I’m the perfect

servant. I know when they’ll be hungry and the food is ready. I

know when they’ll be tired and the bed is turned down. I know

it before they know it themselves.

These lines describe the character of a seemingly (and wonderfully) contradictory individual. They are the words of someone whose entire life is dedicated to serving others, but amidst that invisibility and dutiful selflessness there is a great vanity: the belief of having the power of seeing what others can’t see for themselves. And it is this knowledge, ostensibly, that allows this individual to be fulfilled in her work, and perhaps and more importantly, to feel in control of a social situation (and in fact in the film, a murder mystery, Mrs. Wilson is the murderer but is able to get away with it thanks to her imperceptible machinations).

A fictional servant of English aristocrats may appear to be completely unrelated to a reflection around time and contemporary art. Yet, the art world is a social theater with its own set of expectations and desires, and artists traditionally become the actors who, like Mrs. Wilson, fulfill, pre-empt, fabricate and deliberately upset those expectations.

Despite the fact that artists identify themselves with notions of independence and autonomy, the figure of the artist in the end is inextricably dependent of the social context that the art world provides. It can be argued, without much of a stretch, that the artist is a “servant” of the art world: we feed objects, ideas, sentiments into a particular group of individuals who in turn embrace them or not; we fulfill our identity as artists when we materialize our vision in front of others (one may contradict this statement by invoking the hermit-type artist who rejects society; but even in those cases, the moment we learn about them and about their work, that very contact with others puts them in dialogue with society and, whether they want it or not, puts their work in the service of the art conversation). We service the art world as much as gallery artists as we do as provocateurs, as enfant-terribles, or total rebels to the establishment; this is in fact an entirely expected behavior.

Furthermore a persistent myth about art is that it predicts the future — that is, that the artist operates in a register where he or she captures the zeitgeist of a particular period in a way that anticipates much of what will be thought or felt. The artist, in this sense, strives to become the perfect servant of futurity; trying to learn the gift of anticipation, and thus write the next chapter of the conversation of art.

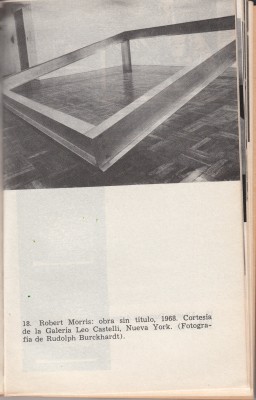

For most of the XXth century, and well into the late 1960s when one spoke about the future of art, the conversation revolved around a few lines of thinking. The first dominant and then discarded discursive line was oriented toward the internal art discourse; that is, a line that looked at the “evolution” of art history as a reflection that would bring aesthetic thinking to its ultimate consequences. The second was related to technology, where the argument revolved around the idea that the advancing breakthroughs in science and communication bring forth a form of art making that takes society into new realms. In both debates there was recognition that art was becoming an inward-looking practice — a practice, perhaps, without a viable future.

In 1969, Guggenheim curator Edward F. Fry organized a series of lectures at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum entitled On the Future of Art, where by his own description they intended to address a problematic situation in contemporary art:

“Even before the end of the 1960s, it was

apparent that the normally endemic crisis

within contemporary art had reached an

acute and problematic stage beyond all

previous dimensions. Critical issues,

which had long remained dormant and

only partially resolved, emerged with a

new urgency, and the very worth and

function of art itself within society were

being questioned by artists themselves as

well as critics.”

Fry, who is remembered in art history today mainly for having been the curator who lost his job by defending Hans Haacke’s proposed 1971 exhibition at the Guggenheim controversial Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Social System as of May 1, 1971; is revealed in this volume as an individual interested in introspection and critique. For that lecture series he brought together Marxists and Structuralists, proponents of new technologies and established practitioners.

Perhaps what is most striking about the lectures on this book is the degree to which the various lecturers gave importance to “correcting course” in art making, feeling that art in the current moment was being misguided in its extreme introspection, its limited reach and what would be lost by its break with historical conventions. The lectures also, as mostly happens with the predictions of the future, did not actively try to speculate much on the actual future of art, as much as with the present problems in art —such as the ultimate implications of conceptual art or art made by computers.

What is also interesting about reading the lectures from four decades ago, from the vantage point of New York in 2013, is how little we think of the future of the art practice today. Today there is much less urgency on thinking about what the future may bring, or worry that art will lose its relevance. It is almost as if the discussion of the future now, like this book, had been relegated permanently to the past. Whether this is because we have given up on the hopes that we can generate a unifying theory on the contemporary art landscape that would help us point to where it may be going, or because we no longer hold such worries that art will stop being relevant or that there is such a thing as the “right path” for art making, the question on what will art bring has lost its philosophical urgency.

*

Tags: Biography, History, Memory, Mexico, Museums, Performance lectures