A Vicarious Learning (2017)

I belong to the last analog generation. I first saw a personal computer when I was 11, in 1982 — an exotic experience not dissimilar to the opening scene of Marquez’s One Hundred years of Solitude when José Arcadio Buendía takes his son Aureliano to see ice for the first time. Our English teacher at my primary school in Mexico City, who was a big proponent of technology, had convinced the school to purchase a handful of computers. They were large, cream colored, mysterious, with green texts blinking on their dark monitors.

By looking at those seductive but still clunky objects, I could have never imagined at the time the degree by which our lives would be transformed and defined by them. And as much as I have enjoyed and appreciated what virtuality has brought to us, my impulses as an artist have always been of restoration, or remembrance, of the feelings and experiences that existed before the digital revolution.

The beginning of my intellectual life consisted in being around books- first the books of my grandfather (who was an aspiring writer at some point) and my father (who was an avid reader and assembled an impressive collection of French literature to improve his language skills). In Mexico City the logical places to visit for books was El Agora in Insurgentes, Gandhi (which has now become a vast chain of bookstores but at the time was barely starting), Librería del Sótano, the Centro Cultural Universitario at the UNAM, and of course the various bookstores that lined Donceles street. As a student, I frequented the Donceles bookstores in particular, both because books were cheap and because I enjoyed the thrill of the chase, the hunting expedition through a labyrinth of books that would eventually yield a gem, a book so valuable that even the bookseller would not know what it was.

To me the relationship with the object of the book was not only educational and practical, but also emotional and symbolic. Perhaps it had to do somewhat with the Mexican intellectual tradition in which I had grown up, where the homes of major writers and poets were packed with books, including the one of my uncle, the poet Eduardo Lizalde, which I visited often to play with my cousin. There were books everywhere, in Baroque excess that resembled a horror vacui of printed matter.

There is a famous photograph of Alfonso Reyes, the “dean” of modern Mexican letters, standing in the middle of his two-story personal library containing some 20,000 volumes, now known as the Capilla Alfonsina. Somewhat, the infinity of books served as a means to showcase the erudition and importance of their owner. And Reyes, a physically diminutive man himself, whose complete works encompass 26 large volumes, was most definitely not austere in his creative output or in his collecting.

There is something important to note about these massive libraries inside the homes of the Mexican intellectuals: while they were essentially private, they all enjoyed receiving visitors and having the opportunity to introduce them to their collections. In every case they constructed their settings, both sanctuaries and headquarters of their vision, from which they would be able to operate.

*

Fast forward to a day in November 1989, in Chicago. The Midwestern cold of the late Autumn has already set in, piling groups of dark brown leaves in the street corners. I leave our family apartment on Campbell Avenue in West Rodgers Park, and wait for the bus. I buy the Chicago Tribune, which on its headline that day displays the news of the fall of the Berlin Wall. I remember reading the news with passion, feeling the significance of that momentous historic event, while at the same time lamenting my condition of distant bystander.

I had just moved to Chicago to study at the School of the Art Institute. My excitement about learning art was starting to give way to a certain frustration, as part of me would have hoped to attend a regular liberal arts college instead. I wanted to experience the atmosphere of the American university campus, with its fake medieval buildings and its leafy courtyards. I had somehow envisioned a social environment of collective reflection and exchange; instead I was inside an art school that promoted individual and rather private exploration in the tradition of the lone genius.

I would have conversations on the phone with my high school friend Carlos Aizenman, who like me had left Mexico to study in the U.S. He had gotten admitted to Brown University, to study neuroscience, and his descriptions of his studies (he was taking a class on Western thought, along with his specialized courses) filled me with jealousy.

I had a burning yearning for knowledge. I wasn’t sure how to attain it, and felt in conflict with my art school education, as I did not care so much about technique but about the world of ideas.

So I would wait for the bus on weekends and go to Evanston — a beautiful suburb of Chicago that is also the location of Northwestern University. I imagined myself studying there (which never happened) and would spend my time walking around that campus, but most importantly, visiting the used bookstores of the area.

For me, a penniless art student with those intellectual aspirations, used bookstores became my oxygen, my lifeblood and my inspiration. I did visit public libraries (I constantly checked out a recording of José Zorrilla’s Don Juan Tenorio in audio cassettes, and memorizing the play in its entirety upon repeated listening). However, the public library was limiting for me: I did not like the rule that the book would have to be returned.

But Mainly, I wanted to develop the sort of deep relationship that Borges had with works of literature, which he would re-read many times, essentially inhabiting them. In reading Borges’ lectures about literature what impressed me most at the time was not the variety of his references, but the depth with which he knew them (Shakespeare, Stevenson, Spinoza). I wanted to reach that depth, which meant that I wanted those books to myself. I would roam those streets religiously ruminating on the words of Sartre, Ortega y Gasset, Bergson— in search for meaning, in search of what I naively described in a student essay of the time, “the continuous dialogue”.

I liked the various small bookstores in the area, as well as their various owners. Most of them were socially awkward (like me during those times; I believe I have improved somewhat), deeply knowledgeable on some very specific subjects and proud of showing off what they knew. One of them, well into his seventies, had deeply black tinted hair and a bald spot that he would try to conceal with what appeared to be black shoeshine.

I found them endearing. These booksellers were individuals who perhaps in another life would have been authors or scholars but due to the vicissitudes of life had ended up behind a counter at a bookshop. I imagined that they were the aspiring authors who never bloomed, the connoisseurs who never made their first It appeared to me that their erudition in very narrow book topics, their strange humor, and their tendency to accumulate literary trivia was a way for them to compensate for not having become the great writers I imagined once they must have dreamt to become.

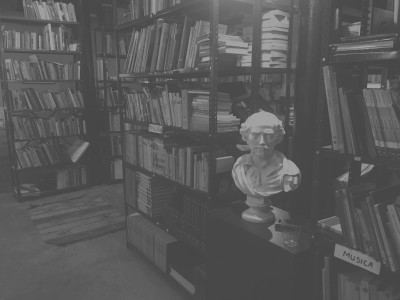

The place that most attracted me was Bookman’s Alley, on Sherman Street, owned by Mr. Roger Carlson—an older gentleman who sat at a messy desk at the entrance of the store. Bookman’s Alley was the typical idiosyncratic shop that, in the spirit of most used bookstores, had the wonderful ambiguity of feeling both like a public and a private space: public as any retail establishment, and private in that it was arranged like the large living room of its owner. You would find all sorts of interesting and strange corners in the store, with typewriters, phonographs, a native American-themed section, and all sorts of varied old furniture in between.

It was at this store where I bought my first copy of The Waste Land, Finnegans Wake, and the Cantos. I encountered the works of the English Empiricists Hume and Berkeley, whose ideas had always interested me after being introduced to them by my brother Nacho.

My encounters with those books were powerful and meaningful. But being an immigrant art student, self-taught, in the situation where I was, the vicariousness of my learnings made me always feel uncertain, not sure if I was on the right learning path.

Precisely because that exasperation of feeling that I lived on the sidelines of the conversation of current art, many years later I left Chicago to New York. I strongly felt that to develop a career as an artist I needed to be in the center of the conversation, in the place where things happen, so that I could actively participate and have my contributions to that conversation be recognized.

But then something interesting happened. I began to value, instead, this kind of vicarious learning, and the important perspective attained by not being at the center. After having lived through the identity politics wars of the 90s and feeling that the center-periphery discourses were cliché attempts to justify an amateur practice, the New York art world also disappointed me at times with its self-importance and blindness toward anything that was not truly at the center.

As I came to see how dominant ideas of art quickly become fashion and then start losing their original shine, I realized how important it was to have practiced this ongoing quest for the obscure. This means that while a multitude of people have read the latest Zadie Smith novel, I might be one of the only New Yorkers who has read the works of Francis Ponge, Felisberto Hernández or La Obediencia Nocturna by Juan Vicente Melo (which incidentally became the title of one of my first solo exhibitions in Chicago). That same quest for obscurity was a source of pride amongst those eccentric used booksellers, and to an extent it could be see just as vacuous as being up to date on the latest New York Times Bestseller. But I felt that the quest was valid when it was fueled by a sincere desire to understand and scrutinize the world.

The explorations of those years continue to inform my work, as a catalogue of references that at times appears inexhaustible. My pleasure in it is not on the fact that these works may be deemed too obscure or hermetic, but that they explore and refer to aspects of our life that are not often reflected upon or spoken about.

This awareness somehow coincided with the clear process of the demise of the used bookstore in New York. When I arrived in New York almost 20 years ago, the city brimmed with used bookstores. Now there hardly a handful of them, all of them on the verge of extinction. One of my favorite bookstores in my neighborhood, on Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, was run by an eccentric man named John (not unlike other booksellers I have known). His bookstore was a complete chaos, the living headquarters of a packrat. Getting through the bookstore was always a challenge. It had no heat in winter, and no AC in the summer, making the experience more akin to being inside a cave. But it was a rewarding cave, and I found many treasures in it over the years. Finally John closed his store last summer. It took months for a trailer to empty the space.

*

In Octavio Paz’s landmark study of the work of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Paz explores the way in which Sor Juana, who lived in the isolation of a convent and within the greater cultural isolation of the conservative colonial society of the New Spain, was constantly in search for knowledge but his access to books was limited to the historic works available at the time (Greek classics, for example) and the writings sanctioned by the Catholic Church (like St. Augustine, for instance). For this reason she would have probably never known of many landmark works of philosophy and science written during her lifetime and then already circulating in Europe, material that was commencing to give shape to the Enlightenment.

? was a certain belatedness about her knowledge — which of course did not prevent her from composing brilliant poetry or expressing ideas that were in fact precursors to modern philosophical attitudes (like the Carta a Sor Filotea). And like Bach, Sor Juana was firmly grounded in an aesthetic Baroque tradition that did not prevent her from producing some of the most important works within that tradition.

I could perhaps not have articulated this at the time, but my intuition was that the kind of belated knowledge that books offered me could not do any harm to me as long as I was aware of the fact that I was absorbing a classical education. During the presidential campaign of 2016, a political commentator said of Bernie Sanders that his ideas sounded like the ones of someone who has spent too much time in the politics section of a used bookstore.

While I am certainly aware and in agreement that expressing or repeating old ideas and trying to apply them to new circumstances might seem ridiculous and tone-deaf, I am equally interested in the use of history to understand the present, particularly as someone who creates something new. The conversations I had with those dead authors were, then, not a desire to simply repeat their ideas but instead to see them in the new light of the reality I was living in. Today, as an artist who has lived and worked in the contemporary art world for three decades, I am further less fascinated by the shock of the new, and recognize also the traps that novelty sets: it is much more important, I have learned, to do something well in whatever format or approach it might be, than do something new.

*

In 2013, When Douglas Walla generously invited me to think of a project at his gallery Kent Fine Art, I had been thinking of the bookstore idea for a while, but I had never given it serious thought. I undertook the journey to Mexico City to start a book donation campaign. After some time, I had a handful of donated books- certainly not enough to start a bookstore. It wasn’t until later, when I managed to get a journalist from the newspaper La Jornada to write a story, when everything changed. People from all over Mexico wanted to donate books. There are two interesting facts to know about the Mexican middle class: one is that people do tend to inhabit the same house for decades, and often for generations. This means that things accumulate in one’s home, including books. So everyone I know had some collection of books to donate. The other fact is that as Mexicans, we are pained by the plight of the immigrant in the United States; people who have been basically orphaned by both governments, and we feel a sense of deep impotence at improving their situation. Librería Donceles offered, in a symbolic but meaningful way, a way for them to contribute to a cause- in this case, the cause of both showcasing the richness of another language and giving access to books to Spanish-speakers. In some ironic way, someone said at some point, a third world country was sending aid to a first world country.

A few weeks later we had 20 thousand volumes to bring to New York. The setting up of the store was intuitive for me; I had never set up a store in my life before (although my father was a businessman and had a showroom in the garage of our house, and I do recall enjoying setting up a desk there and becoming part of “the staff”). As I progressed in the store’s décor, all the bookstores I had been to in my life started coming back to me. I also realized, after setting up a few lamps and rugs on the space, that I was more or less recreating my Mom’s apartment in Chicago— a domestic interior that truly transports oneself from a nondescript suburban American apartment to a turn of the century house in Mexico City. I ended up fully embracing the idiosyncratic sensibility that I saw in every bookstore I remembered, placing family photos, ashtrays, and basically anything I liked as if it was my own house.

After New York, the bookstore traveled to seven different cities: Miami, Phoenix, San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago, Indianapolis, and finally Boston. Its itinerancy became an expected feature, but more important than anything was the social space it created. Communities all around the cities where we set up shop congregated there.

I have done socially engaged art projects for about 15 years, and I have worked as museum educator for around a quarter century. Never in all this time had I experienced a project in which the visitors would be so visibly and positively altered, making personal connections and investing themselves so much in what we had to offer. Also, in this age in which national politics have used xenophobia as a vote getting strategy, it is more important than ever to show that opening oneself to other cultures is inifinitely enriching.

We may not be able to expect every American to learn another language, but that is why books exist. That analogue “window to the world”, that I grew up with before I knew any other windows, before I could travel anywhere and learn about the complexity of the world, carried me then and still carries me now. It took me to Russia in the XIXth century, it took me to Moorish Spain, and it took me to revolutionary Mexico. And it did so in a physical and sensorial way that to this day I can’t replace. I have always been fascinated by the amount of world contained in single book, and I want other to see it.

Librería Donceles is, for me, a tribute to vicarious learning. It is the university for those of us who couldn’t attend one, it aims to be the warm social space that other places of learning lack; it is a cultural parenthesis in another language; it is the living room in an immigrant’s brain. It doesn’t have the aspirations or the pretension to confer degrees: instead it offers more primal, and long-lasting forms of learning and experiencing that depend on social interaction and communication.

Thank you, John. Thank you, anonymous Chicago bookseller with whom I once had a long discussion on the word “fungible”. Thank you, Mr. Roger Carlson, wherever you might be, for having created this world of windows for me to visit.

Tags: Biography, Chicago, Education, Identity, Language, Libreria Donceles, Nostalgia